Playground Society

Tor Lindstrand plays in the city

The work of Lefebvre, Baudrillard, Foucault and Deleuze is invoked as a prism through which to consider the manner in which the space of the city is shaped, controlled and regulated. This extends too to Neoliberal readings of Jane Jacob’s theories. But these thinkers – along with the references to Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison, the background of a Bruegel painting, and the utopian hopes of Drop City during the 60s – have, in Tor Lindstrand’s view, much to tell us about a very specific type of activity in the city: play.

The lineage of post-war approaches to playgrounds in the contexts of Sweden and the UK in particular evidence a complex history of play in the city and continue to inform many contemporary approaches to public space and “regulation” of the urban environment. Within this discourse, there have been voices urging for play to be taken seriously. Colin Ward, for example, author of 1978’s The Child in the City has argued for the manner in which children encounter and respond to – play with – the built environment to be drawn upon during the process of designing urban space. Through paying attention to this significant proportion of the urban population, creativity rather than control becomes the guiding factor.

However, this emphasis on play has been borrowed by actors arguably less concerned with the process of relating pedagogy within the city and more concerned with the initial spectacle of a game. Many contemporary projects tended towards an appropriated version of the idea, namely: playificiation. (It’s not by accident that the term readily conjures that other “-ation”, the “gentri” variety.) This tendency has benefited particularly from the new layers the city has comes to acquire since Ward wrote his seminal book; today, the urban environment is endlessly represented and performed in digital form on social media. New York’s High Line project, for example, widely seen as a milestone in urban “regeneration”, can also be read as being akin to a Facebook feed: an elevated strip from which to consume the city below. Play can serve as a way to engage with and become directly involved with the city; playification runs the risk of reinforcing a disconnect with that same context.

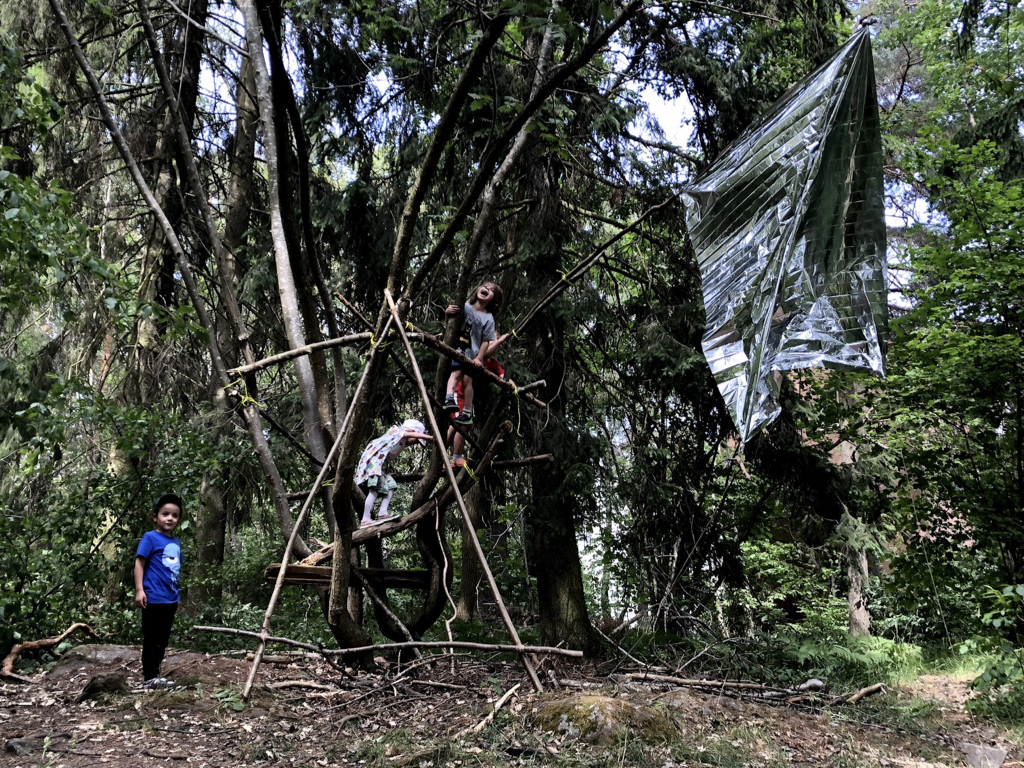

In addition, unlike its more distanced cousin, play is subject to ever more stringent safety regulations. In many countries, the rules are so tight that it is almost impossible to build a playground from scratch on account of the vast raft of pre-existing rules that prohibit many pieces of equipment or their arrangements. But, who is this overemphasis on safety really for? As the urban environment is shaped in such a way that prohibits play, spaces of playification step in to offer their services. The urban shopping mall, for example, a dying breed in the post-Amazon world, has begun to reinvent itself as a site of play, albeit one underpinned by consumption. This trajectory is undeniably disturbing but, as Lindstrand’s Making Futures workshop sought to encourage, it can also be read as an opportunity: a phenomenon for the practitioners to – quite literally – play off against.

Tor Lindstrand is an architect and Senior Lecturer at Konstfack University College of Arts, Craft and Design in Stockholm, Sweden. We invited Tor to deliver a workshop entitled “The Playground Society” as part of our plug-in at the Floating University in June 2018.